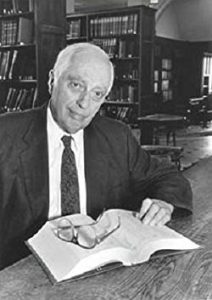

Bernard Lewis, a prominent historian of the Middle East, has died at 101. He was a towering figure of Middle Eastern studies in Western academia but also a controversial scholar whose essentialist view of the region encouraged and justified the Western intervention.

Dr. Lewis was a prolific author whose more than 30 works shaped Western views of the Middle East. He was the leading Western scholar of Turkey in the twentieth century. His groundbreaking work, The Emergence of Modern Turkey, is still an essential reading to understand the Turkish transition from empire to republic. It is fair to say that his perception in Turkish scholarship was completely different from his image in Arab studies. He said once, “For some, I’m the towering genius. For others, I’m the devil incarnate.”

Many saw Bernard Lewis as an enabler of Orientalism and Islamophobia. He was the scholar who coined the term “clash of civilizations” later elaborated by Samuel Huntington. Another controversial topic in Dr. Lewis’s long career was his opposition of naming 1915 as “Armenian genocide.” Dr. Lewis was accused of minimizing the genocide and seen as a genocide denier.

A few years ago, Dr. Lewis published a memoir titled Notes on a Century: Reflections of a Middle East Historian. In this book, the historian looks back on his long career, his academic studies, his dreams, and regrets. After the publication of the book, I had an opportunity to interview him. At the time, Dr. Lewis was residing in an assisted-living facility and answered my questions with the help of his partner, Buntzie Churchill.

Although Dr. Lewis underlined that the book is not an autobiography, it is an account of his life. “It is a chronologically arranged sequence of experiences, recollections, and reflections,” Dr. Lewis said, “It is certainly not complete, and it deals only to a very limited extent with my personal life. It also contains short discussions of my views on various issues some, but not all of them, still current.”

Regarding dedicating his life to the study of the Middle East, he had no regrets: “I have learned to appreciate other cultures, other civilizations, other times, other places, other peoples but remain at peace with who and what and where I am.”

‘MY EARLIEST AMBITION WAS TO BE A WRITER’

One of the revealing parts of our interview was about youth dreams. In the book, Bernard Lewis occasionally mentions his interest in poetry and literary translation. When asked whether he would prefer being a poet or a novelist instead of an eminent historian, he confessed that his initial life plan was different: “My earliest ambition was to be a writer. My study of history gave me something to write about. Poetry is about feelings. Novels are about imaginary characters and events. History is about real people, real events – and historians describe and discuss them.”

Bernard Lewis was not only an influential historian but also a witness to history. As a young student, he learned Turkish in Paris from Adnan Adıvar, a prominent Turkish scientist who was in the close circle of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Republic of Turkey. With his wife, the novelist Halide Edip, Dr. Adnan Adıvar lived in exile in the 1930s. Dr. Lewis recalled Adıvars and his Paris days: “I did meet Halide Edip, but only socially – and briefly. She was an immensely impressive person. Adnan Bey was a dedicated and effective teacher and was one of the formative influences in my life. He introduced me to the range and depth of Turkish literature for which I have always been grateful.”

A FRIEND OF TURGUT ÖZAL

His relationship with Turkish elite continued later on when Lewis was teaching Middle East history at Princeton University. Bernard Lewis was a good friend of Turgut Özal, the 8th president of Turkey who died in 1993. “I met Turgut Özal long before he became a well-known politician. We liked each other and got along well. Like other distinguished guests to the US two stops were compulsory, Washington and New York. Princeton lies between them. I persuaded him to stop over. He met with faculty and students, and their reaction was very positive,” said Dr. Lewis.

Talking about the current status of Middle Eastern studies in the West, he suggested that Edward Said’s impact is enormous and his disciples control almost everything. Isn’t such a claim inaccurate and unfair? Dr. Lewis did not think so: “The Saidian view is an enforced orthodoxy in most, but not all, departments of Middle East studies. Fortunately, the opposition to Said is growing and spreading. Facts and logic will, in the end, prevail – even in the academic world.”

What stroked me most in the book is Lewis’s sense of humor. Does he agree that sense of humor is a dispensable attribute for a true intellectual? “Some form of humor is an essential part of any civilization,” said Lewis, “The joke is sometimes the only form of criticism or dissent that can be expressed in authoritarian societies – that is, in most of the world and in most of history. It is instructive to be able to laugh at a joke from a long time ago and a long way away. The themes are so often the same but sometimes contrasting. For example, mother-in-law jokes occur in both eastern and western societies but on one side the theme is what a man suffers from his wife’s mother and the other is what a woman suffers from her husband’s mother.”

When asked about his opinion on the civil lawsuit against him in a French court because of the Armenian genocide denial, he said: “I am neither a citizen nor resident of France and since these absurd proceedings I have not been and will not be a visitor. These problems are therefore no concern of mine but I think they should be of concern to any self-respecting Frenchman. The trials were a painful experience, but they were not one of the most important phases of my life. Historical problems should not be resolved by legislation. The attempt to do so is both absurd and pernicious.”

In the book, Dr. Lewis quotes Sadiq al-‘Azm’s remark about the future of Europe: “Will it be an Islamized Europe or a Europeanized Islam?” I asked Dr. Lewis about his prediction. “I am not a prophet or the son of a prophet,” he told, “I am a historian. I deal with the past, not the future.”

Bernard Lewis was worried about Turkey’s direction. He argued that the country is not very secular anymore and he had doubts about the future of democracy in Turkey. (A few years later, he is sadly proven right.) Finally, I asked him his thoughts about Turkey’s future. Dr. Lewis shrugged: “As I said, I am a historian. I deal with the past, not the future. The Turks must decide where they are going and by what route.”